Institutional Design: What do ALADI, Mercosur and UNSAUR have in Common and what does it tell us about South American Regional Organizations?

After having described the Mercosur and European Union Sisyphus’s negotiations in a previous blog post, another Greek mythological figure appears in the study of South American international relations: Cronos. The Titan used to eat his offspring because he was afraid to be overthrown by one of his children. Analogously, ALADI, Mercosur and UNASUR States Parties seem intimidated by their own regional institutions and look to be ready for a banquet. This blog post presents some PhD research conclusions on institution design and regional integration in South America.

ALADI (Latin American Integration Association), Mercosur (Southern Common Market) and UNSARU (Union of South American Nations) have adopted an intergovernmental approach to regional integration. These South American states’ design choice is the result of their historical disputes (both colonial and post-colonial), preponderance of the executive branch at the national level and their difficulty to articulate and bargain on a regional level in order to achieve decisions that could be accepted by all States Parties.

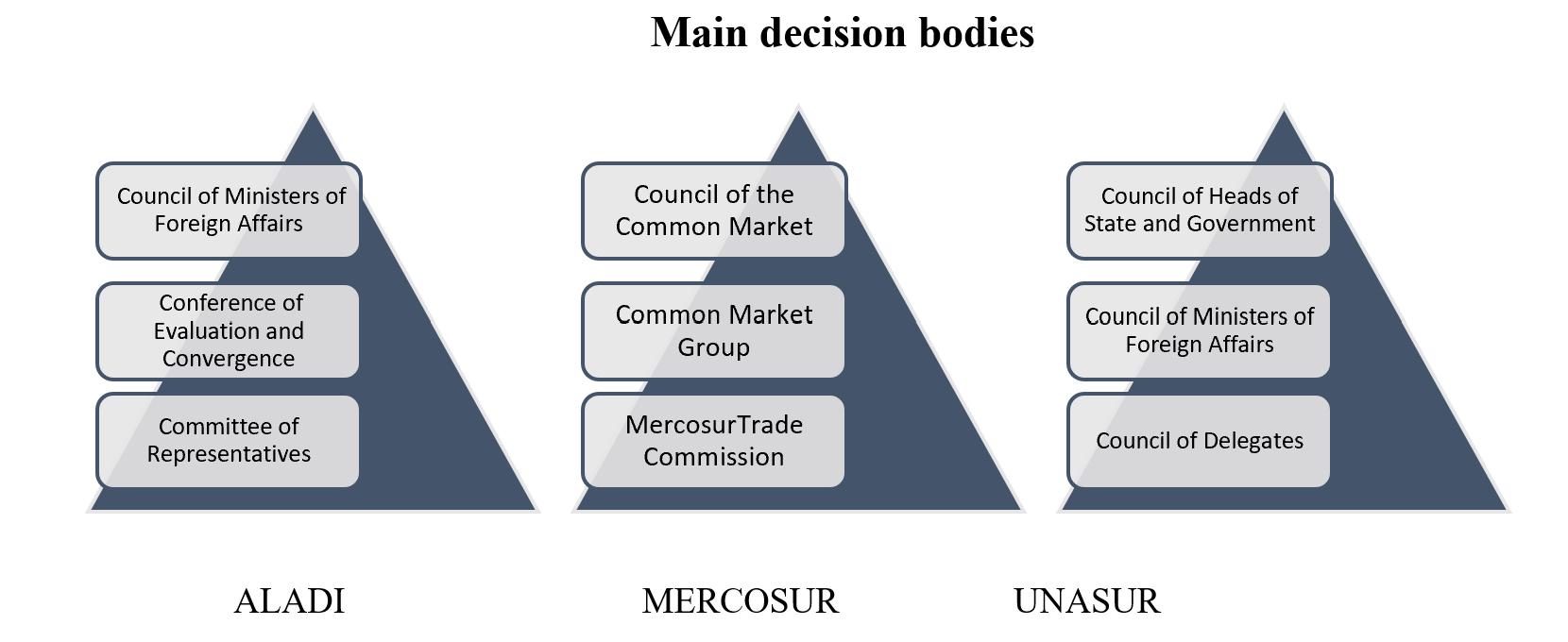

There is a tendency in South American integration processes to adopt consensus-based decision-making processes as a way of equalizing states’ interests, lest they oppose a decision, exercising veto power. The institutional structures of ALADI, Mercosur and UNASUR reflect that tendency. The three international organizations have six shared institutional traits: (1) intergovernmentalism as a paradigm; (2) adoption of consensus with the presence of all States Parties as a quorum for decision-making; (3) direct action by the Ministries of Foreign Affairs of the States Parties in defining the agenda and in policy-making bodies; (4) hegemony of (national led) Executive organs; (5) inexistence of a binding jurisdictional body; and (6) dispute settlement procedure based on direct negotiation and mediation by States Parties representatives.

The intergovernmental features of these three integration processes have been adopted and developed over the last forty years: ALADI since the 1980s, Mercosur since the 1990s and UNASUR since the 2000s. This institutional design allows states to control the agenda, placing those with greater and lesser relative power on an equal footing. Thus, it is evident that the intention of these institutions designers was to maintain states’ power and sovereignty over the regional agenda, not forbearing the organization to exercise any level of autonomy.

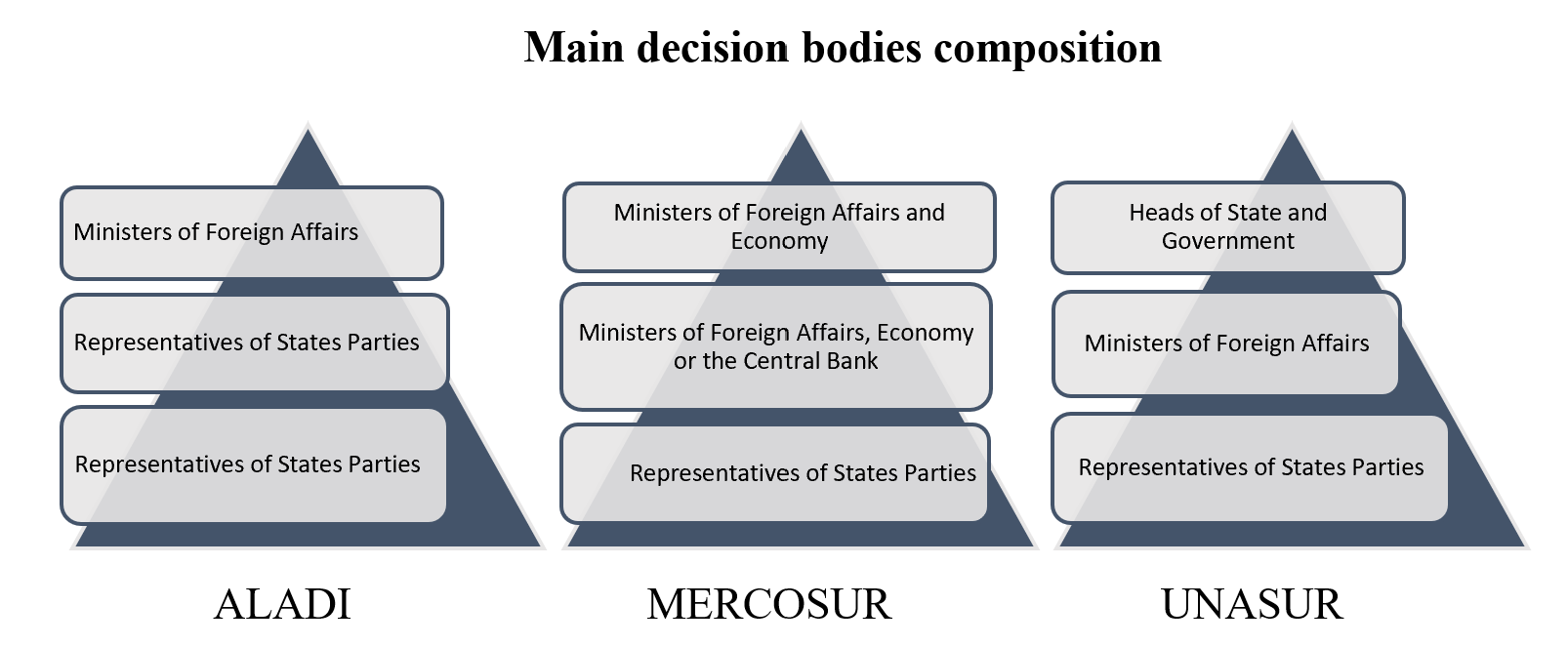

All of ALADI, Mercosur and UNASUR decision bodies are composed of representatives of the Ministries of Foreign Affairs or Heads of States. This structure gives the State the autonomy to place matters of direct interest in the agenda, without the sieve of an autonomous regional body. In other words, the definition of regional policies rests on the countries themselves, as shown below:

By substituting the bodies names by their composition, the pyramids can be drawn as follows:

It is also important to note that their constitutive treaties define in different ways (that is, with different expressions) the format for their decision-making.

Nevertheless, by looking closer, it can be inferred that the States consent is always required.

By assigning one vote to each state and adopting the consensus rule, these models prevent the regional organization from exerting sufficient influence to determine or at least guide the path of the integration in opposition to the direct interests of the States. In other words, ALADI, Mercosur and UNASUR are not endowed with a will of their own, being in reality an interstate negotiation forum. In addition, the decisions adopted, in the same way as latu sensu international treaties, go through a process of negotiation, signature and ratification. What differentiates the general treaties procedure from that adopted by ALADI, UNASUR and Mercosur are that in these there is a thematic specialization within the organization, which is a forum established in advance by the States, possessing an institutional culture on certain subjects.

All main decision-making bodies are composed of representatives of the States Parties, especially the Executive Branch. The supremacy of the Executive Branch is confirmed by the fact that the organs are composed mainly of Heads of State, Ministries of Foreign Affairs or Economy. Furthermore, besides the consensus rule, most parts of legislation adopted by the integration organizations need, mandatorily, to pass through the process of internalization, which entails the perception that they are not autonomous bodies, rather negotiation forums, equipped with an established institutional structure.

Regarding the dispute settlement system, none of the three organizations has a strictu sensu jurisdictional body, that is, one that can state the law and enforce its sentences upon the states. Moreover, the three integration organizations adopt direct negotiations as a form of dispute settlement, followed by mediation by a regional body. This mediating body, as seen, is formed entirely by representatives of the Executive of the States Parties, in particular by members of the Ministries of Foreign Affairs.

Hence, it can be said that both direct negotiations and mediation are carried out directly by the States themselves. In Mercosur, States have the additional possibility of resorting to two arbitration fora (Ad Hoc Arbitration Tribunal and Permanent Review Tribunal). These fora are composed of national arbitrators from the States Parties, previously indicated for a standing list. In any case, the appointment and choice of arbitrators are also carried out by the States themselves. Both Mercosur and Unasur constitutional treaties create regional parliaments, however they play a small role in the organization and have very limited power. For instance, Mercosur Parliament can only propose projects and its decisions are non-binding.

The main shared aspect of these South American integration organizations is their objective. In other words, as the States intend to bring the countries of the region closer together and establish relations in order to overcome historical grievances and divisions, they conceive of and carry on a certain model of integration process. Official discourse is that these countries share values, history, perspectives and interests. Despite this rationalization, given that the design of institutions prioritizes control by the States to the detriment of the creation of a supranational organization, it is possible to see an everlasting degree of distrust, even mistrust, among them, although their relations are increasingly converging. Thus, the South American model of integration presents itself as a model designed almost not to integrate, or, rather, an idealized model to allow States to strongly control the speed and deepening of the process of integration.

As stated earlier, the three international organizations resemble Cronos’ tale. Despite having conceived those institutions, States Parties seem to be afraid that someday they could somehow take over and become autonomous, so the States keep them inside their wombs, only to be later eaten. That is the reason we must remember that Zeus (one of Cronus's descendants) was able to grow up and defeat his father. The actual role of the aforementioned regional parliaments may be paltry, nevertheless, this may be the silver lining.

Elisa de Sousa Ribeiro Pinchemel is a Visiting Research Fellow at Institut Barcelona d'Estudis Internacionals, IBEI (2022). Researcher at Mercosur Research Group from UniCEUB (since 2008). Researcher at Geo$mundo - World Economic Geography from Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná (since 2016). Researcher at Study Group on Law and International Affairs From Universidade Federal do Ceará (since 2021).