Voluntary Sustainability Standards and Market Transformation towards Sustainability. Trends and Challenges

In September 2015, the United Nations Member States adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development which comprised a new set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Market-based tools like Voluntary sustainability standards (VSS) are expected to play an increasingly important role in complementing governments’ efforts towards achieving these goals. In essence, VSS aim to foster more sustainable and transparent practices among actors at all levels of global value chains, hence contributing largely to achieving SDG 12 on sustainable consumption and production among other SDGs.

However, the recent COVID-19 has slowed down economic growth, increased unemployment, and even raised poverty and global hunger, rolling back the decade long progress to achieve the SDGs. One crucial issue the pandemic highlighted is the vulnerability of societies to risks affecting the health of people. Other health concerns are associated with how we produce, consume and trade products, and to the social and environmental consequences of these activities. Thus, it is even more important now to put the SDGs at the heart of policy making.

The recent launch of the 4th United Nations Forum on Sustainability Standards (UNFSS)[1] Flagship report on ´Upscaling VSS through Sustainable Public Procurement and Trade Policy´, which we wrote, provides policy making scenarios to expand and rethink socioeconomic models that do not compromise the three pillars of sustainable development and complement the widely emphasized need for improvements in public health systems. The integration of VSS in public procurement and trade policies are potentially powerful means to upscale the adoption of VSS.

The report focuses on the adoption of VSS by refering to the degree of its uptake by producers or firms along the global value chains. This can be measured by different indicators, such as the total number of VSS schemes that are active globally or in selected countries, the number of producers or firms that are certified, the number of certified hectares of production land, and the proportion of certified products per commodity.

VSS adoption trends and dynamics

Sustainability is not a new phenomenon. It appeared for the first time in 1987 in the famous Brundtland Report (also known as ´Our Common Future´) produced by several countries for the UN. The trend for sustainability standards picked up further thereafter with the introduction of the Dutch Fair Trade standard, Ecolabels and standards for organic food and products.

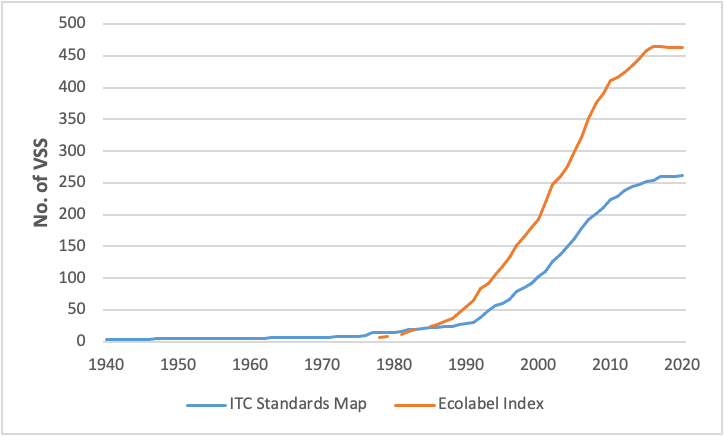

Today, there are over 400 of such standards. Figure 1 shows the number of VSS in operation captured by the ITC Standards Map and Ecolabel Index.

The Flagship report identifies two trends. First, although the idea behind VSS is quite old, their proliferation is more recent: VSS truly emerged in the 1990s, and their number grew consistently until the early 2010s. Second, growth in the number of active VSS has been slowing down in recent years , though it is unclear why this has happened.

Figure 1: Evolution in the number of VSS active worldwide, 1940–2020

Source: Authors’ calculations based on ITC Standards Map[2] and Ecolabel Index.[3]

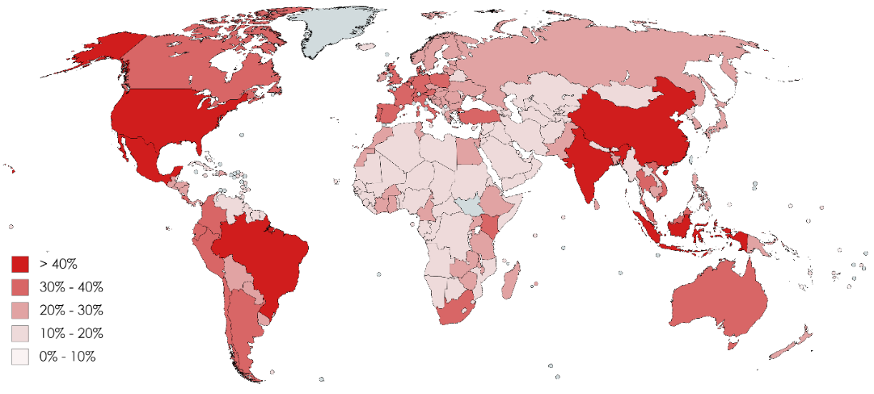

These VSS are, to different degrees, active in countries across the world. The Map below shows the degree of adoption by country measured as the percentage of active VSS in a specific country in relation to the total number of active VSS worldwide.

Map 1: VSS adoption intensity map per country (as a percentage of all VSS)

Source: Authors’ map based on ITC Standards Map[4]

Several observations can be made:

- VSS are found in all countries, but there is considerable variation between countries.

- Variation in adoption levels appears to more or less align with income levels.

- While variation in adoption levels does not always perfectly align with income level, there is also variation between similar countries in relation to VSS activity.

- Some lower-middle-income countries score high, such as Viet Nam, Indonesia and India.

- Even some low-income countries score fairly high, such as the United Republic of Tanzania and Ethiopia.

Concerning the evolution of certified commodities, the Flagship report shows that certification has intensified over the past decade, in terms of both the proportion of certified commodities in their respective markets and the proportion of certified production area. However, publications also indicate that while certification is gaining grounds, overall, only a limited amount of land is certified. For example, often less than 5% of agricultural land of some commodities are certified.

These trends indicate that there is still quite some scope for increasing adoption of, or upscaling, VSS. But how can this be achieved? The report looks to the role governments can play via sustainable public procurement and trade policy.

Sustainable Public Procurement

Who are the biggest buyers in any market? Governments. Several sources estimate that government procurement accounts for up to 15% of an economy’s GDP in high-income countries, and even higher in middle-income and low-income countries. Hence, the purchasing power of governments can provide real incentives to nudge markets towards higher standards of sustainability and upscale the adoption of VSS. This can be pursued through so-called sustainable public procurement (SPP).

In recent years, SPP has developed and been widely adopted by public authorities throughout the world. Through SPP, governments can ensure that public contracts contribute to broader environmental and social policy goals.

It envisages public authorities demanding, for example, that their purchases of wood products are manufactured from legally harvested or sustainable timber, that public buildings meet ecological standards, that clothing for State employees is made in a healthy labour environment devoid of child labour, or that coffee served by public bodies is produced under fair conditions. Hence, via SPP, governments can deliver key policy objectives related to sustainable development.

In the rise and growing importance of SPP, VSS can play a specific and increasingly significant role since they are often integrated into the operationalization of SPP practices. In public procurement, VSS operate on the basis of an elaborate set of rules and procedures to ensure that producers and all actors in the supply chain conform with social and environmental standards.

However, the development of SPP policies does not imply a straightforward recognition of VSS by governments, as they need to assure equal treatment, non-discrimination and fair competition among public procurement tenders.

Yet, VSS may be referred to indirectly in SPP through the inclusion of sustainability criteria in public tenders that are similar to standards set by VSS, or by making reference to VSS as a form of proof of compliance with the criteria stipulated in tenders. As a result, in daily procurement practice, VSS serve as indicators of social and environmental performance, and may be used as a convenient means of assessing a bidder’s credentials.

While, overall, VSS are gaining recognition in SPP, the question remains whether such recognition can lead to greater VSS adoption. Several examples highlighted in the Flagship publication suggest that SPP could indeed increase VSS uptake. Yet, further considerations on upscaling VSS adoption through SPP include the need to set up of recognition systems in order to distinguish credible from non-credible systems.

Trade policy

With the rapid increase in global trade in the past few decades through global value chains, trade governance has gained importance. Multiple instruments are used to govern global trade flows, many of which can influence the uptake of VSS. The Flagship report identifies four types of trade-related instruments in which VSS already play a role or whose role is under consideration by States. These are free trade agreements (FTAs), preferential trade agreements (PTAs or GSP schemes) market access regulations, and export promotion measures.

FTAs have evolved over time, both in number and in content. Over the last decades, we have observed a strong increase in the number of FTAs, with 301 currently in force. Moreover, FTAs have evolved in terms of content, as they increasingly incorporate non-trade objectives such as sustainable development provisions, or social and environmental protection provisions. This also includes references to the use and promotion of VSS. In the Flagship report, we identify 19 FTAs which refer to the use of VSS. However, currently, such provisions remain promotional rather than conditional as they do not require clear commitments and involve little permanent evaluation. There is therefore considerable scope for further integration of VSS in FTAs.

A second trade instrument into which VSS can be integrated are (PTAs, or more specifically, generalized schemes (or systems) of preferences (GSP). A GSP scheme is a preferential trade arrangement by which a country grants unilateral and non-reciprocal preferential market access to goods originating in developing countries. Among their objectives, both VSS and GSP schemes aim to foster sustainable development and good governance and, hence, some authors propose to further integrate VSS in GSP. The Flagship report discusses the possibilities and limitations, pro’s and con’s of such further integration.

A third trade measure that could have a significant impact on VSS uptake is market access regulation. There is no general overview available on how many regulations exist which include VSS in market access requirements, but some recent examples show how this is currently done. The report discusses several examples including the European Union Timber Regulation, which was developed in the context of the EU’s 2003 Action Plan on Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (FLEGT) and the Korean Act on the Sustainable Use of Timbers amended in 2017.

A fourth trade-based instrument into which VSS are and can be further integrated are export promotion measures. VSS can contribute to increasing access to markets, and hence promoting exports. Governments can engage with VSS in different ways to increase exports. The Flagship discusses several examples including the cases of cotton in Mozambique, timber in Gabon and shrimps in Suriname. While these examples provide little evidence on the outcomes of the inclusion of VSS in export promotion measures, they nonetheless serve to identify different types of government engagement with VSS in those measures. First, governments can make certification a necessary requirement for obtaining an export license. Second, they can provide financial incentives for certification in order to promote certain export-oriented sectors and products. Third, they can engage with VSS to provide training and capacity-building to producers in order to help them increase their exports.

So, there is ample scope to upscale VSS and governments could play an important role in this. But is it a good idea? In the final part we would like to reflect on some of the issues one needs to consider when upscaling VSS.

Integrating VSS into sustainable public procurement and trade-based instruments might significantly influence their adoption, but it also raises a number of issues. These include capacity issues within VSS systems, the possible impacts resulting from the growing number of VSS, the implications for recognition systems, the risk of over-certification, and possible distributional effects. This blog discusses each one of these implications.

Capacity of VSS. Most VSS schemes recognize organizations that are responsible for accrediting certification bodies to perform assessments of conformity with standards. Yet, the Flagship report highlights that some VSS remain actively engaged with certified entities in order to ensure compliance with standards. This might imply that some VSS can only certify a limited number of companies and are not necessarily interested in certifying as many as possible. A VSS governance model which only involves independent certification bodies for granting certificates and handling complaints can therefore more easily cope with a significant increase in demand should VSS be further integrated in public policy. However, even in these cases, a sharp increase in demand for certification could pose challenges, such as a lack of time to conduct proper and correct audits, an insufficient number of qualified auditors, and/or ensuring that the auditors are sufficiently competent.

Increase in the number of VSS and recognition of VSS. VSS are currently concentrated in a few sectors (mainly in the agricultural sector) and there are no (or very few) VSS for products obtained through public procurement. Further integration of VSS in public policy might therefore lead to the creation of additional VSS, which could in turn create confusion on the market and see an increase in VSS that are pure “greenwashing”. A proliferation of VSS also raises the question whether a regulatory framework should be developed which deals with the recognition of credible VSS. While there have been calls on the WTO to adopt such a framework, it could also arguably disrupt the voluntary nature of VSS. This leads us to a third point.

Convergence and divergence of recognition systems. Recognition systems to distinguish between credible and non-credible VSS are currently emerging and generally involve requirements related to three different dimensions of VSS schemes: (1) what standards are set, (2) how standards are set and enforced and (3) value chain requirements or tracking methods. Yet many recognition systems might therefore emerge, all with more or less similar requirements, but also possible small differences in requirements. This might make it difficult for VSS schemes to comply with the diversity of recognition systems. The Flagship report thus highlights the importance of considering actions to create convergence between recognition systems.

Over-certification. VSS do not necessarily aim at certifying as many companies or producers as possible, but rather at creating certified markets. Hence, a key challenge for them is to have enough buyers in consumer markets. Integrating VSS into public policy might thus generate too many certified goods of which not all will be sold or marked as such on the market. There are some indications that there is already an oversupply of some certified products on the markets and some certified products are thus being sold without a certificate, which defeats the very purpose of VSS.

Distributional effects. Lastly, it is important to consider possible distributional effects of upscaling VSS adoption. Studies have shown that VSS could potentially be a catalyst for trade, but also a barrier. Indeed, being certified involves two types of additional costs for economic operators: the cost of becoming certified, and the costs related to adjusting production practices in compliance with VSS standards. These costs can undermine the ability of producers – typically from least developed countries (LDCs) – to comply with or adopt VSS. This problem, which is referred to as “stuck at the bottom”, results in some producers in LDCs being excluded from VSS dynamics and from export markets. Considering VSS in public policy might therefore bring such distributional effects.

To summarize, the 4th UNFSS Flagship proposes five key steps that countries can take to integrate VSS into public policy:

- Enhance national capacity through a governance model that involves independent certification bodies to cope with rising demand for

- Incorporate VSS within the trade regime with a database that uses the Standard International Trade Classification to provide an overview of the commodities covered by the standards.

- Avoid the proliferation of VSS systems through ensuring convergence of recognition mechanisms.

- Curb over-certification through appropriate measures.

- Conduct political dialogue on the benefits of scaling up VSS.

Axel Marx is Deputy Director at the Leuven Centre for Global Governance Studies, KU Leuven.

Santiago Fernandez de Cordoba is Senior Economist at United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

To read the full 4th Flagship report, see: http://unfss.org/home/flagship-publication/

[1] UNFSS is an initiative of five United Nations agencies, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the International Trade Centre (ITC), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO). UNCTAD is the secretariat of UNFSS.

[2] ITC (n.d.). ITC Standards Map. Available at: https://sustainabilitymap.org/standards?q=eyJzZWxlY3RlZENsaWVudCI6Ik5PIEFGRklMSUFUSU9OIn0%3D (accessed, March 2020).

[3] Ecolabel Index (n.d.). Ecolabel Index. Available at: http://www.ecolabelindex.com/ecolabels/ (accessed, March 2020).

[4] ITC (n.d.). ITC Standards Map. Available at: https://sustainabilitymap.org/standards?q=eyJzZWxlY3RlZENsaWVudCI6Ik5PIEFGRklMSUFUSU9OIn0%3D (accessed, March 2020).